"There's a tendency to forget about the mailroom," he says. But that message has yet to be received in many security departments. Day says that CSOs have an important role to play in ensuring mail security. Thomas Day, vice president of engineering for the USPS, has seen his job transformed by the anthrax attacks from a focus on expediting the movement of mail to strengthening the Postal Service's defenses against future attacks.

Since the attacks, the Postal Service has taken the lead in educating private companies and citizens about the standards and practices that are fundamental to good mail security, offering onsite consultations to help companies improve their security procedures. And another facility in Trenton, N.J., underwent an $80 million cleanup and is expected to reopen by the end of 2004.

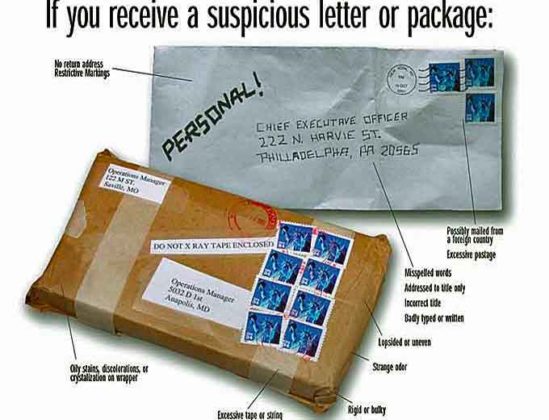

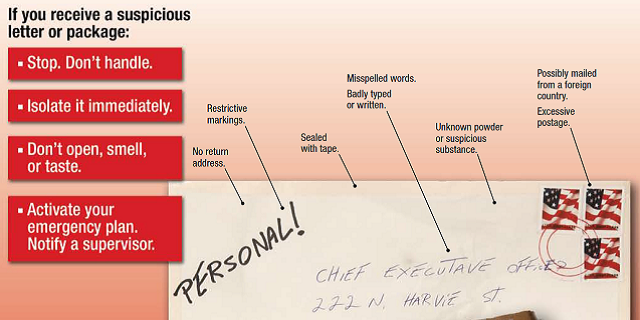

The Brentwood postal facility in Washington, D.C., required a $130 million decontamination and renovation before finally reopening in December 2003. Two postal workers died from inhalation anthrax in 2001, and another seven survived exposure. They used to make people wear gloves, but why should they now? Nothing's happened." Guevremont estimates that only 3 percent to 5 percent of private industry is currently prepared to handle a mail-borne security threat.įew organizations understand the stakes of mail security better than the United States Postal Service. "It's been so long between incidents that people have become lackadaisical again. Senate, House of Representatives and Department of Defense. "It's out of sight, out of mind," says Mike Guevremont, senior vice president with Executive Protection Systems (EPS), a security consultancy that provides WMD protection equipment, training and services to the U.S. Many of the precautions that companies put in place were phased out after the initial crisis passed, and in most companies the mailroom work is once again considered just another rote administrative task with few or no security implications. WHAT A SUSPICOUS PACKAGE LOOKS LIKE: A parcel or letter is considered suspicious when it has more than one of the following characteristics: strange return address or none at all unusual weight, given its size, lopsided or oddly shaped excessive postage odor, discoloration or oily stains marked with restrictions, such as "Personal," "Confidential," or "Do Not X-Ray" an unusual amount of tape handwritten or poorly typed address, incorrect titles or titles with no names, or misspellings of common words.Īlthough 22 infections and five fatalities were eventually attributed to anthrax exposure, three years have faded much of that initial fear into a melodramatic memory. The evening news was filled with images of Americans donning gloves and face masks for the short walk down to the mailbox. A spate of white-powder hoaxes followed, and across the country companies supplied latex gloves and detailed procedures for their employees to use when opening mail. Politicians, celebrities and thousands of regular folk scrambled to get their hands on the small white pills. Of course, NBC wasn't the only entity caught up in the hysteria. Brokaw's assistant had tested positive for exposure to cutaneous anthrax and much of NBC's New York staff, including the usually unflappable anchor, was put on the anthrax-fighting drug as a precaution. When Tom Brokaw held up his amber prescription bottle in October 2001 on NBC Nightly News and declared, "In Cipro we trust," the statement encapsulated the nation's vulnerability during the anthrax scare. Leave it to Tom Brokaw to make the statement for mailroom and postal security.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)